Someone once told me that having a child was like having your heart beat outside your body. At the time my daughters were babies and the statement resonated so strongly that I shivered. Sure, it was metaphor, but the visceral experience of love for my daughters made it feel literal.

The day my first daughter was born, I realized that I would instantly run into a burning building, dive in front of a truck or otherwise give my life to save hers. This new depth of connection felt utterly natural and mostly wonderful, but also scary.

As a family medicine resident in the early 1980s spending 110-hour weeks in an always-full safety net health system, I was regularly reminded of the many dangers that can befall infants and children. Even the thought of my baby girls dying of SIDS or succumbing to meningitis made me physically ill. These fears were not acute – except when one of the girls came down with a fever or started throwing up – but I became aware of a low-level anxiety whenever they were not in my sight.

When my first daughter was a few weeks old, we placed her basinet in the next room and her mother and I listened to her breathing – more honestly, we listened for her breathing – before being able to sleep. Soon we were entrusting her to a babysitter and as time passed to daycare and preschool, followed by overnights with friends and weeks at summer camp – memories that now seem like an amusing highlight reel of parental sleep disturbance. And then they were no longer little girls and started going out on dates and next thing I knew I was dropping them off at college! I adjusted, absorbed a lot of “Oh Dad” eye-rolling, and we all grew through it. But “I wonder how the girls are…” has been the ever-present crawl across the bottom of my consciousness screen.

My daughters are now both independent, successful women. Yet my fatherly instinct to protect them from hurt and harm is undiminished. I know it’s unrealistic, that it’s impossible to live fully and be unscathed by loss and misfortune, but that’s all the more reason to try.

What does this have to do with advance care planning? Everything.

In an article I called, Because I’m a Dad, I explained that having an advance directive is a way of extending my fatherly caring into a future when I will be the object of attention – and emotional distress. Envisioning such scenes, I imagine that my daughters might wish for my arm around their shoulders.

So, after filling out the required sections of my advance directive, I added a handwritten message to my wife, daughters and the rest of my family, which says (paraphrasing for brevity here), “If you are reading this and I am seriously ill, my deepest wish is for you to be gentle and loving with yourselves and one another. Please support one another and know that I love you, and trust you, and will accept whatever treatment decisions you make.”

That note was influenced by something I learned from Dr. Joe Fins. In a seminal essay, Commentary: from contract to covenant in advance care planning, Fins observed that advance directives are built on the chassis of legal contracts which, by design, do not assume trust and exist to protect parties from negligence or malintent. And yet, most people want decisions about their care during future infirmity to be made in trust by people who know them and love them. I later joined Dr. Fins in a study to test this hypothesis. We presented people with difficult (but common) hypothetical cases that tested resolve in strictly following either “do everything” or “just keep me comfortable” instructions in a person’s advance directive. Sure enough, when faced with a life-or-death situation, a majority said they would trust those they appoint to make the right decisions for them, even if those decisions overrode the letter of previous instructions.

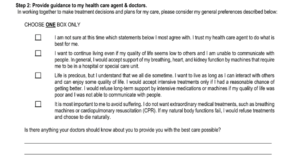

These findings and perspective inform our efforts at the Institute for Human Caring of Providence St. Joseph Health to improve advance care planning at scale. Working with our corporate legal team, colleagues and I recently designed a short-form advance directive that has just three sections and can be completed in moments. Section 1 lists the name and contact information for one or two individuals whom the patient trusts to speak for them. Section 2 has four boxes with statements of general health care preferences to advise the health care representative and future doctors as they make decisions. [[see text box]] Section 3 is the person’s signature in the presence of a notary or requisite witness(es). This short form can complement a more expansive advance directive toolkit we offer in the seven Western states Providence St. Joseph operates.

While satisfying the legal requirements of advance directives, this shorter document is notably more covenantal than traditional forms. By avoiding a living will style menu of treatments – mechanical ventilation, dialysis, and medically administered nutrition – the options in Section 2 are less bound to specifics of future hypothetical situations and, therefore, may be easier to endorse. But importantly, the first box states: “I am not sure at this time which statements below I most agree with. I trust my health care agent to do what is best for me.”

These state-specific short advance directives are just being rolled out across the Providence St. Joseph Health system. Time will tell whether people find these redesigned forms easier to complete. We’ll be closely monitoring completion rates. No doubt we’ll find things to improve in the months and years ahead.

Whether I’m periodically updating my own advance directive or working to improve quality across a health system, I’m aware that advance care planning draws on the best attributes of fatherhood. For one thing, it never ends. Honoring people’s wishes and protecting them from harm are open-ended commitments. For another, taking the best care of people during inherently difficult, stressful times entails supporting people to take care of each other. Most important of all, as a doctor who is also a father, I am continually reminded that decisions about treatments are never just medical; they are always intensely personal. The people affected are only incidentally patients – they are foremost family members. Paternalism sometimes gets a bad rap. At its core, being paternal entails embracing responsibility and looking after people skillfully, wisely with tenderness and love. At its best, advance care planning, like being a father, is a matter of heart.

Ira Byock, MD, is Founder and Chief Medical Officer of the Institute for Human Caring within Providence St. Joseph Health. His books include Dying Well and The Best Care Possible. More information is available at IraByock.org and InstituteForHumancaring.org

Such a smart young woman. Excellent advice, will follow thru.

I love the way the author paints his feelings about his children; very touchy and authentic;

Preparing Advance Directive is a great advice!

Ira,

Sensational piece – as always. I can relate to the parental angst and love how you have converted it into its root – our passion for our children! Way to help us find new ways to translate that passion as we and they grow. I’ll be sharing this for sure!

Peace,

Tom