“If I ever end up like that, just let me go,” my dad declared. “I don’t want anything to do with a feeding tube or any of that nonsense.”

My father’s statement about his grandmother was familiar to everyone at my parents’ house that day. Some families are reluctant to talk about their end-of-life care wishes. Not mine. I’ve been present for countless conversations like this. My parents and most of their siblings and cousins are over the age of 60, and assertions like my father’s are part of the routine at any gathering.

These discussions of illness and death used to make me roll my eyes, until I realized they were missed opportunities.

A variety of end-of-life experiences

The passing of their parents and grandparents gave my mother and father a range of experiences with death. My dad frequently cites the end of his grandmother’s life — prolonged by a feeding tube against her children’s wishes — as the worst way for someone to die. My mother lost her parents in two separate (and unexpected) events over a 20-year period that devastated her family, and robbed them of the opportunity to make end-of-life care choices.

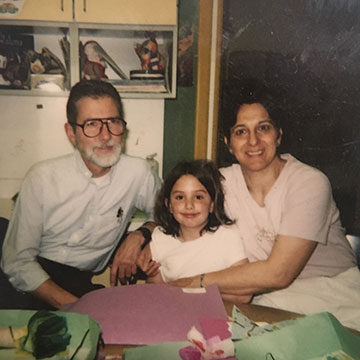

My paternal grandfather passed away last April. He experienced the model of what you might call a “good death.” His health had been deteriorating for three years, and when we realized he had reached a point from which he would not recover, we transferred him to hospice care. He had a wonderful and peaceful final week with his family and loved ones.

Discussions of these end-of-life experiences — and those of other family members and close friends — made it comfortable for me, at age 25, to talk about death with my parents. I thought I had a pretty good idea of what they would want for their end-of-life care.

However, when the topic came up for what seemed like the umpteenth time at brunch recently, I realized that’s all I had — “a pretty good idea” of what my parents want. I had seen no official documentation of their specific guidance or designation of a spokesperson in case they are ever unable to speak for themselves. Where are their health care proxy forms? Do they have advance care directives? Who has copies?

In case of an emergency, I suddenly wasn’t so sure if my sister and I could be confident about carrying out their wishes. “Just let me go” isn’t particularly helpful advice for making life or death decisions. When? Under what circumstances?

Getting the details

Realizing that my sister and I needed more information, I asked my parents to fill out The Conversation Project Starter Kit. I also decided it was important for me to start this process for myself. I read The Conversation Project’s How to Choose a Health Care Proxy & How to Be a Health Care Proxy guide, completed the Massachusetts health care proxy form, and appointed my sister to speak for me if I’m ever unable to speak for myself.

If your family is as comfortable as mine talking about death, hopefully sharing openly and in more detail about what matters most at the end of life will be relatively easy. If your family may be less open to this discussion, try to initiate a conversation around your own wishes. It may open up communication that goes both ways, and their responses may surprise you.

Whether you open this discussion or deepen it, you’ll be taking an important step that could one day provide immeasurable reassurance and support for your loved ones. Make sure that you, like my family, are not just talking, but having The Conversation.

I would like to start a conversation “its not good enough” just let it go. I am glad my grandmothers and family member are familiar with my ways of telling you anything is good enough for your family and to love yourself. I understand I have a pretty good idear of what i want my kids to understand. You should and find different ways and ideas of self determination and different ways on how to carry through your life. Don’t ever understand for anybody to let you go.