When we are no longer able to change the situation, we are challenged to change ourselves.

—Victor Frankel, Man’s Search for Meaning

Malcolm was sitting up in bed, his hospital door ajar. He had on headphones, and his slender body kept time to the music. The window shade was raised, letting the afternoon sun flood the room. He didn’t hear me knock, but noticed movement at the door and waved me in. As he removed his headphones, I recognized the familiar coda of “Hey Jude.”

He was in his early seventies, wearing flannel pajama bottoms and a worn tee shirt with a familiar image emblazoned across the front: the cover of the famous Beatles album Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. His hair was unkept and his face unshaven. By way of introduction, I acknowledged our shared love of The Beatles. He smiled, held my gaze for a moment, and said softly,

“Their music has been the soundtrack of my life.”

With his pain under control, Malcolm had been moved from the intensive care unit to a step-down unit, where there would be less commotion to disturb his final days. Only five years earlier he had been on this very floor, recovering from a life-saving liver transplant. Sooner than hoped, his body had grown weary of the donor’s priceless gift.

Malcolm comfortably talked about his recreational drug use and the hepatitis C that eventually claimed his liver. His gratitude for the donor and transplant team that had given him these extra years was palpable. He appeared content. I acknowledged his calm presence and asked if he was a religious man.

“Not so much,” he said easily. “I’ve thought about it for a while and decided that being an atheist is more my speed.”

“I’m curious what led the way, if I might ask?”

“That’s easy,” he said. “John Lennon.” He thought for a moment and recited, “Imagine there’s no heaven… No hell below us, above us only sky…”

“What a classic,” I chimed in. He agreed with a smile.

When I asked about his prognosis, again quite comfortably he told me the doctors had suggested treatments that might prolong his life. He had weighed the benefits of more time and the burden of needing to be closely tethered to the hospital and had decided to forego further treatment. He shared it matter-of-factly, yet it struck me as radical, particularly given the setting.

He was referred to the palliative care team, who help patients to manage their symptoms at any stage of an illness. For Malcolm, they were supporting him in the precious time that he had left.

“I’ve done everything I wanted to do,” he said. His genuine acceptance held my attention.

I asked if he’d share some highlights. Number one was visiting England with his sweetheart.

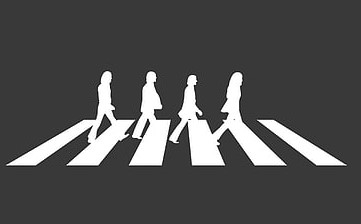

“We did Liverpool and a pub crawl tour where the boys first came onto the scene. John and The Quarrymen! It was awesome. We had such a great time we went back the next year… We joined a tour of Abbey Road Studios, the Beatles’ old recording studio in London. At the end, we walked out to the famous crosswalk, where fifty years ago the Boys were photographed strutting across Abbey Road. We followed suit. We were walking on air.”

His words drifted into stillness.

Years ago, Malcolm had discovered something that was important to him and embraced it fully. While I was finding meaning and purpose in Sunday School, Malcolm had found his elsewhere. I admired and acknowledged his quiet alliance.

Earlier in the visit, he shared that as his major organs continued to fail and his appetite waned, he had changed his code status from “Full Code” to “Allow Natural Death” (AND). [Editor’s note: Code status refers to which interventions a person would want in an emergency. For example, Allow Natural Death, also referred to as “Do Not Resuscitate” (DNR), tells the health care team not to try to revive the person if their breathing or heart has stopped.] He was weary, yet at peace, as he reflected on the long and winding road. I gleaned that he was curious to find what lay ahead and asked him about it.

“It’s been a good life,” he said. “I don’t have much time left, but that’s how it goes…”

Pausing, again with a telling smile, he added, “All things must pass away…”

Patients will usually signal when they’re ready for a visit to end. I thanked Malcolm for his trust. He thanked me in turn, saying that he felt seen. I got up and turned to go, stopping halfway to the door. During clinical pastoral education, my fellow chaplains and I were encouraged not to leave a room without offering a blessing. Perhaps you already know what came to mind — wanting to honor what Malcolm held most dear. I offered three immortal words, the title of a song that’s holding up well against the test of time: “Let It Be.” Through his tears, with the room shimmering in light, Malcolm recited the song, word for word, each verse resounding with an echo of reassurance and timeless wisdom.

One of David White’s favorite resources from The Conversation Project is the What Matters to Me Workbook, designed to help people with a serious illness get ready to talk about what is most important to them. He is the author of We Need to Talk.

Want to keep connected to The Conversation Project? Sign-up for our newsletter(s), follow us on social media (Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, YouTube) download our conversation starter resources and feel free to reach us at ConversationProject@ihi.org.