Portsmouth, N.H — Lydia Valdez was 8 years old and getting ready for bed one night when she casually asked her mother a question from across the room.

“Mom, do you think if I died now, would God let me see myself as a teenager?”

It was 2012, and Lydia was 15 months into what would be a 25-month battle with cancer.

“I knew a door was opening,” her mother, Paula Skelley, recalled recently from her home here. “And I remember telling myself not to let it shut. No matter how hard that was.”

Conversations about the end of life are hard for most people. But they can be especially sensitive for parents guiding children through terminal illnesses. They often struggle to discuss death because they don’t want to abandon hope; children, too, can be reluctant to broach the subject.

But pediatric specialists say the failure to discuss death — with children who are old enough to understand the concept and who wish to have the conversation — can make it harder for all involved.

A conversation could help children who are brooding silently suffer less as they approach death. It would also ensure parents know more about children’s final wishes.

“It’s not easy, but it really helps,” said Dr. Jennifer Mack, a pediatric oncologist at the Dana-Farber/Boston Children’s Cancer and Blood Disorders Center in Boston.

End-of-life conversations are perhaps more accepted than ever before. For the first time, Medicare this year is reimbursing physicians for discussions with patients about their preferences for care at the end of their lives. Living wills, which can be used to specify individuals’ medical wishes if they are incapacitated, have become commonplace.

Paula Skelley displays a photograph of her daughter Lydia Valdez, on January 21, 2016, in Portsmouth, New Hampshire. Lydia was 8 years old in this photograph, which was taken for her participation as a “pedal partner” in the Pan-Mass Challenge. (Kayana Szymczak for STAT)

But the subject of death and how to prepare for it has remained largely off-limits when it comes to terminally ill children.

Pediatric specialists say there are myriad reasons. It’s often hard to predict a child’s response to life-saving therapies and, therefore, the timing or likelihood of a child’s decline. And sometimes children with terminal illnesses, like adults, experience what clinicians refer to as “middle knowledge,” where they vacillate between accepting and denying their possible death, thereby making it hard to know when to start the conversation, said Dr. Anna C. Muriel, a psychiatrist who works with the pediatric oncology team at Dana-Farber/Boston Children’s.

Skelley said she was worried about having a conversation about death with Lydia, but she was more worried about not having it.

“I thought about the vulnerability of being that young, wanting to discuss something so badly, and thinking it’s not OK to talk about unless the adult did,” Skelley said. “It was a flash in my head, like ‘I have to do this.’”

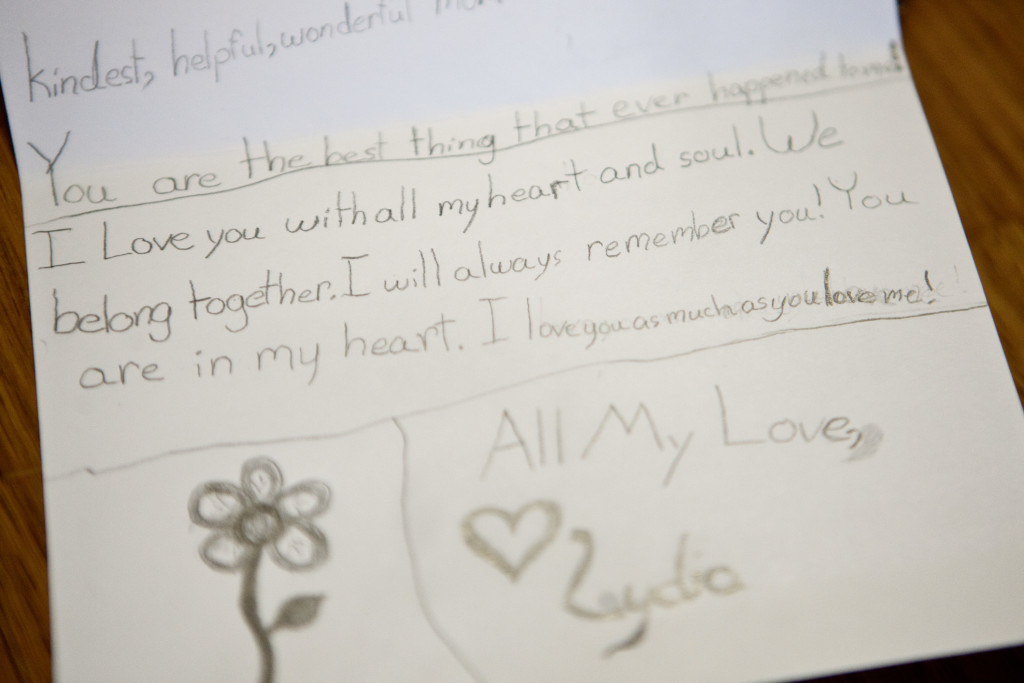

A “love note” that Lydia Valdez wrote to her mother, Paula Skelley, 6 weeks before she died. Paula said she wrote her many notes in the various journals that she would draw in everyday while she was sick. (Kayana Szymczak for STAT)

When Lydia asked whether God would let her see herself as a teenager, Skelley said, “I thought, ‘Now’s my chance. It’s casual. We’ll keep the casual tone.’”

Skelley told her daughter she believed God would grant her wish if she asked. She then asked her daughter if she thought she’d want to be cremated if she died, so her mom could keep her ashes.

“Mom, you wouldn’t want a dead person in your house!” she said, then laughed. After another moment she said, “I think I’d want to be buried at the cemetery by the school. And I want a white coffin. With bling.”

“Once that door was opened, it was easy for Lydia to bring up a question now and then. It was no longer taboo,” Skelley said. “I’d never blame anybody who hasn’t talked to their child about it, but I had no clue how many benefits there’d be.”

Parents often take cues from doctors when considering how to broach medically sensitive topics, but doctors acknowledge they, too, often avoid the subject of death, or they fail to communicate effectively.

“We get anxious walking into the room. We feel sad this is happening,” Mack said. “All these things can get in the way of listening in an open way.”

But Mack and other pediatric oncologists said children are often thinking about the possibility of death long before anyone else broaches the topic. “It’s just that the topic hasn’t been given any air,” she said.

Paula Skelley, mother of Lydia Valdez, poses for a portrait with a “memory quilt” made from Lydia’s pajamas and bathrobe, in her home on January 21, 2016, in Portsmouth, New Hampshire. (Kayana Szymczak for STAT)

Palliative-care specialists said that nurses who work the overnight shift are often the first to hear children discuss their own death. Lynne Showers, a nurse for 28 years at the inpatient oncology unit at Boston Children’s Hospital, said it’s no wonder why: “Sometimes to sit in a dark, quiet room and relax without the call lights ringing, without the babies screaming next door. There’s just a calmness about the night shift.”

One child, she said, knew she might die within days but told Showers that neither parent had acknowledged it. “It was like the elephant in the room. When that happens, the child will worry about their parents, like ‘What’ll happen to them when I’m gone, if they won’t even acknowledge that I’m going?’”

Showers spoke to one of the parents separately, and told the parent that the daughter was concerned about how they would hold up after she died. The parents talked with their daughter shortly after, and Showers said the family dynamic shifted noticeably.

“About three hours before she died, she pulled me in and hugged me for like a minute, saying, ‘Thank you for everything you’ve done,’” Showers said. “I’ve thought a lot about that hug.”

Skelley said her daughter found similar relief through their conversations. Her own mother had died a year earlier, making it easier for Skelley to talk with Lydia about how that grieving process worked. “My mother’s death gave her a way to gauge what grief looks like after someone you love dearly dies,” she said.

Left: Skelley displays a drawing that was used to build a memorial sculpture in honor of her daughter. Skelley named the drawing and sculpture “Smiling Through the Brokenness.” The sculpture is part of “Lydia’s Garden,” a space dedicated in her memory, located on a section of the playground of her former school, the Little Harbour School in Portsmouth. Right: Skelley stands beneath the memorial sculpture. (Kayana Szymczak for STAT)

In Lydia’s final days, Skelley said, they were able to speak freely about death, their relationship, their shared pain, and their confidence that they would see each other in heaven.

These conversations helped eliminate any guesswork that might have surrounded Lydia’s preferences for her care. She chose to go home when she knew the hospital had exhausted its treatment options. She told staff members she loved them, and she thanked people for what they had done to help. She died in April 2013.

“After Lydia died, I was not faced with horrendous choices to make while in the depths of despair,” Skelley said. Lydia chose her burial place, her coffin, and the teddy bear she wished to be buried with.

Making these decision empowered her when she was otherwise powerless. And as important as such things were, Skelley said their open acknowledgement of death served more critically as a way for them to ease each other’s pain.

“If we’d never had that very first conversation, she wouldn’t have let me know when the time was near. It would’ve been too big,” she said. “We would’ve been alone in our grief while sitting in the same room, rather than sharing our grief and, in a way, overcoming it together.”

“Instead we could hold each other. And that was a gift.”

Paula Skelley stands at her daughter Lydia’s gravesite bench in the South Cemetery on January 21, 2016, in Portsmouth, New Hampshire. Lydia’s gravesite is directly across a small pond from “Lydia’s Garden”, a memorial space dedicated to her which is located on a section of the playground of her former school, the Little Harbour School. Lydia specifically requested to be buried in this cemetery to be close to her school. She was buried right in front of the grave of a young girl, Hannah, who’s gravesite inspired the initial end of life conversations that Lydia and her mother eventually had during Lydia’s struggle with cancer. (Kayana Szymczak for STAT)

Read the full article by Bob Tedeschi here.